Suborder: Oniscidea

Phylogeny

This is an isopod. You might know it as a

woodlouse, pillbug, sowbug, doodlebug, or

roly-poly. Isopods are crustaceans, which is a

group within the Arthropods. Insects, arachnids,

and trilobites (sadly extinct) are also

arthropods. Most crustaceans, including most

species of isopod, live in the ocean--crabs,

lobsters, etc. Terrestrial isopods are one of

the few land-dwelling crustaceans alongside land

crabs. Barnacles (another crustacean) are

classified as marine even though many spend a

good amount of time out of the water.

There is a lot of scientific controversy, it

turns out, regarding the phylogeny of the major

arthropod groups.

Domain: Eukarya (everything with a nucleus)

Kingdom: Animalia (animals)

Phylum: Arthropoda (animals with jointed legs)

"Subclass:" Crustacea (actually a polyphyletic

group)

Class: Malacostraca (most of the familiar

crustaceans)

Order: Isopoda (crustaceans with lots of feet

that look the same)

Suborder: Oniscidea (terrestrial isopods)

You also might remember this picture from the

older days of the internet. These are giant

marine isopods, but unfortunately the bag of

Doritos is a photoshopped addition. The largest

giant isopod species typically grows up to 14

inches long, and has been confirmed to 20

inches.

They are really popular in Japan.

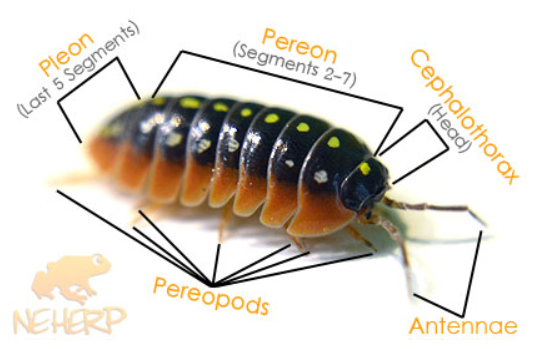

Isopods have 7 pairs of legs that all look the

same, giving rise to the name iso-pod

(equal/identical-foot). All arthropods have a

cuticle (exoskeleton) made of chitin, the same

glucose-derived polymer that makes up mollusc

shells and fish scales. Fungi also have cell

walls made of chitin. The cuticle of an isopod

is divided into overlapping segments. These

segments are called pereonites on the thorax and

pleonites on the abdomen. Like insects, isopods

breathe through their cuticle. Insects have

holes called spiracles to let in air, which are

sometimes visible to the naked eye. Isopod

spiracles are internal and can't be seen from

the outside. Some insects have wax layers on

their cuticle to conserve moisture, but isopods

don't, so they must live in humid environments

to keep from drying out.

Life History

You can find wild isopods quite easily by

digging in the dirt virtually anywhere. They

will be small and grey, usually without distinct

patterns. Some species curl their bodies into a

tight ball when threatened. This is called

conglobating and is patently adorable. They are

detritivores, so they live in the soil breaking

down organic matter. Isopods have been shown to

increase nutrient content and decrease acidity

in forest soils. For this reason they have

become a common addition to bioactive terraria,

where they act as part of the cleanup crew that

recycles animal waste, eliminates unwanted

fungus, and keeps the soil healthy. They are

also used as feeder insects for pet

reptiles/amphibians. A booming isopod industry

has grown up around this practice. The isopods

available for sale online are generally bigger

and prettier than the common isopods you'll find

outside. They're also expensive, so why would

people pay for isopods when they can go outside

and collect them for free? Well, some people do

use wild isopods, but those who opt to buy them

do so for hygiene concerns. Wild isopods can

bring in diseases or pests (fungi, bacteria,

viruses, nematodes, mites, protozoans, etc.)

that could harm the soil biome or any larger

animals you plan to keep in your terrarium such

as amphibians and reptiles. They could also

house plant pathogens that will threaten your

terrarium's live plants. Store-bought isopods

are raised in clean conditions and should never

be exposed to such pathogens. Plus, they are

much more fun to look at.

My Very Own

Species: Porcellio laevis

Latreille, 1804

Last Fall I bought a culture of isopods off Ebay.

I wanted them for a bioactive tank I built for

my crested gecko. I'm going to write a full post

on that project soon. The isopods I bought are

called 'Dairy Cow' for their cute

black-and-white pattern. They're large isopods

with 2 pairs of antennae and 2 appendages

sticking out the back, and they can't roll into

a ball. All those features are common to the

genera Porcellio and Oniscus,

which are known as the sowbugs. Technically any

isopod outside of these 2 genera can't correctly

be called a sowbug.

There is a growing community of people who keep

isopods as pets. They breed flashy new types

just like any pet trade.

I'm not sure if I consider mine pets, but these

suckers are pretty cute.

Even if you don't want to keep them as pets,

rearing isopods can be a lucrative business.

They require very few inputs, very little care,

and they sell for high prices. I paid $23 for 15

isopods, which was one of the cheaper rates I

was able to find. That comes out to $1.53 per

isopod, or $ per pound if we assume the average

dairy cow weighs blank pounds.

Here is my humble isopod home. It's a small

plastic box with holes in the lid for air. I put

down a layer of jungle mix terrarium soil

(basically just a rich dirt), then the sphagnum

moss the isopods came in, then a layer of leaf

litter. I tried feeding them bits of raw carrot,

which they nibbled on a little, but they seem to

prefer the leaf litter. I scooped up leaves from

my local forest floor, trying to get ones that

looked already half-decomposed to give my

buddies a softer meal. I included plenty of

magnolia and oak leaves, since those are the

ones often touted on isopod care pages. I boiled

the leaves in water a few minutes to kill

pathogens, waited for them to dry and cool, then

added some leaves to the isopod box. You can see

the skeletonized leaf veins where the isopods

have been eating. I've also been pruning my

houseplants and adding the dead leaves to the

isopod's food--a wonderful little system. The

box holds humidity very well, but I give it a

water misting every couple days. Many dedicated

isopod keepers use larger glass enclosures

decorated with bark and plants, but mine seem to

be doing fine in their little box for now.

Reproduction

About 2 weeks after my isopods came, I opened up

the box to find tiny baby isopods running around

the leaf litter! I'm proud (perhaps overly so)

to be a successful isopod breeder. There seem to

be a multitude of the little guys, and I hope

the colony continues to grow. Isopods generally

reproduce sexually, though a few are

parthenogenic (female give rise to more females

without mating). Females lay the eggs into a

pouch called a marsupium

How many babies? How long to hatch? Donít have

last body segment or pair of legs at first

The larvae look very similar to adults, with no

dramatic metamorphosis. In insect we would call

this an Ametabolous life cycle, characteristic

of the more primitive insect lineages

(silverfish). Contrast this to Holometabolous

insects like beetles and butterflies, or

Hemimetabolous insects (no pupal stage but still

a different appearance) like grasshoppers and

true bugs and dragonflies.

Update since adding them to the tank. It's been

about 3 months? I don't ever see them crawling

on the surface of the leaves, but I go in

occasionally and dig through the soil gently to

check on them. There seem to be plenty of

various sizes, so I think the colony is breeding

just fine. I add more dead leaves every now and

again, and some orange peel, but they don't seem

to go through food very fast.