Species: Fagus grandifolia

Ehrh.

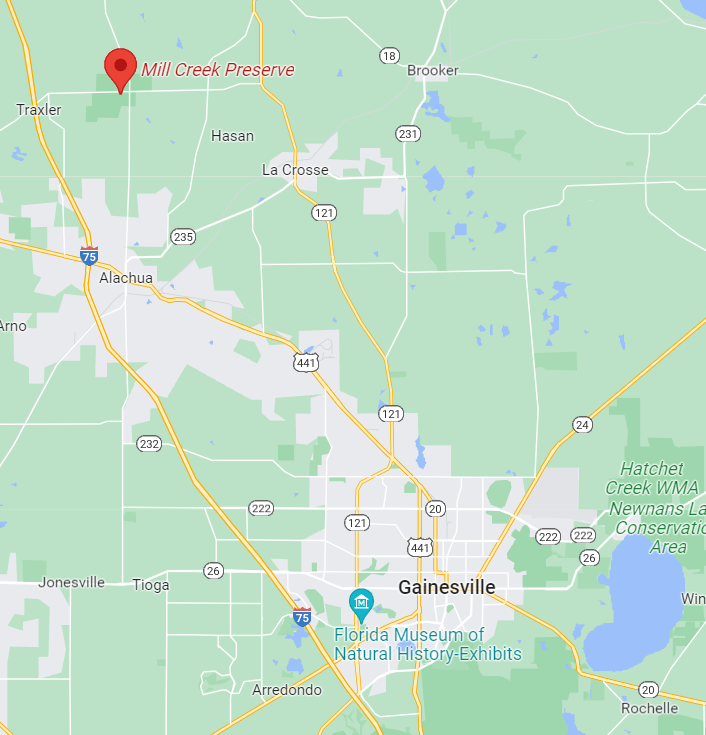

Recently I explored Mill Creek Nature

Preserve for the first time, and encountered

the southernmost population of American

beech trees. I was particularly excited

because I've read all about beech trees in

Peter Wohlleben's book The Hidden Life of

Trees. It's a wonderful little book that

has completely changed the way I think about

trees, and I would recommend it to everyone.

Wohlleben has experience with European

beeches, which are fascinating trees with a

number of incredible adaptations. They talk

to each other, feed each other, encourage

their offspring to grow slow and straight,

and create their own microclimates. America

isn't known for its sprawling forests of

massive beeches the way Central Europe is,

but our beech trees still have a stately

look about them, at least from what I gather

on Google images. The specimens in Florida

are quite small and scraggly, likely because

this is the hot extreme of their temperature

range, so they are outcompeted in this

landscape by oak, magnolia, sweetgum, and

others.

In Europe the American beech is known as

large-leaved beech, and it used to coexist

alongside the common beech in Europe until

it was wiped out in the last ice age.

Mill Creek is a large forest, and I'd like

to go back in summer and explore some of the

other trails when the trees are in full

flush. There were many interesting trees you

don't usually encounter on Gainesville

trails, and many were labeled, but I think I

went down the trail backwards from the

intended direction because I didn't

encounter any labels until the last part of

my trip. The pockets of beech were marked on

the trail map. I went along enthusiastically

inspecting every unknown broadleaf tree,

everything with serrated leaves, convinced

I'd found a beech. Beech leaves can be

difficult to tell from hophornbeam, river

birch, white ash, and others. A surefire

identification method is the underside of

the leaf, which is covered in silky hairs on

a beech. This is known as pubescence, which

sounds gross but just means it's hairy. It's

quite soft to the touch. What is the

evolutionary purpose of these hairs? Might

have something to do with conserving water

during gas exchange.

Beech leaves sit on their branches in broad,

flat planes, giving the whole tree a tiered

appearance like a well-pruned bonsai. The

leaves are large, with an ovate shape that

starts and ends with tapered points but

flares out wide in the middle. They are

smooth medium green on top, with distinct

veins that run all the way to the margins.

The margins are serrate, but not hugely, and

you could miss it if you're not looking for

it. Contrast this with the exaggerated

serrations of the river birch leaf, which is

smaller with a wider base narrowing to a

triangular point. Or the hophornbeam, which

has fine sawtooth double serrations (smaller

teeth between the larger teeth).

Other interesting plants at Mill Creek

include cinnamon fern, parsley haw, horse

sugar, gallberry, musclewood, wild olive,

and sparkleberry. Fun fact, many common

blueberry varieties are derived from

Florida's native Vaccinium species

such as highbush blueberry and sparkleberry.

Sources

Wohlleben, Peter. The Hidden Life of

Trees. Greystone Books, 2015.

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/fagus/grandifolia.htm